Arnold Springer, the man responsible for bringing the two teams ofdoctors to Mongolia, finds solitude at Gandan Hild monastery one early morning in Ulaanbaatar. Springer is a longtime political activist, professor of Russian history at Cal State Long Beach and director of private Ulan Bator Foundation. He set up the foundationto bring Mongolia's "concepts of space, light,air (and) horizons" to West Los Angeles and conversely to bring a better understanding of the West to Mongolia. ©Gail Fisher Los Angeles Times

The Naadam festival fills the fields outside Ulaanbaatar with a tent city as families come to the capital for the festival. Mornings are a step back in time, embracing openness and hospitality, traits that draw Arnold Springer (top) to the country, and inspired him to found his Ulan Bator Foundation in Venice Beach. The group of doctors take in the experience. ©Gail Fisher Los Angeles Times

The doctors enjoy the experience of the traditional Naadam festival, and see it through various perspectives, sometimes through a window driving in a truck. ©Gail Fisher Los Angeles Times

July's annual Naadam festival, celebrating Mongolia's independence from China in 1921, centers on traditions such as horseback riding. Contestants, ages 4 to 11, race over about 15 miles of open countryside. ©Gail Fisher Los Angeles Times

The countryside is marked by remote beauty and hot, dusty summers. These children find relief from the heat by stripping down and playing in a creek bed near the families' gers- the typical nomadic homes that are easily broken down and moved. ©Gail Fisher Los Angeles Times

The medical centers throughout Mongolia lack state of the art resources. " I want to have a significant exchange of medical people between both countries. I want them to come back here and apply what they've learned and work with us to transform the hospitals." ...Arnold Springer ©Gail Fisher Los Angeles Times

The Mongolians are nomadic, living off the land, their children hearty and rugged. ©Gail Fisher Los Angeles Times

Anchig Oidov, 17, a young scholar in Russian languages, traveled from the Gobi desert to see help from American doctors forcongenital arthrogriposis - which means his joints seize up so that he can't straighten his hands or walk without crutches. There's a chance surgery in the U.S. can make him more functional, and able to use a computer. ©Gail Fisher Los Angeles Times

Two teams of doctors from Southern California spent part of July helping Mongolian doctors try to improve health care both in the capital of Ulaanbaatar and in regional hospitals such as this Soviet-era clinic in Central Province, some 45 miles outside the capital. ©Gail Fisher Los Angeles Times

Dr. Robert Greenburg, a retired Newport Beach obstetrician-gynecologist, uses the nonprofit Medicine for Humanity to try to cure cervical cancer in developing nations. ©Gail Fisher Los Angeles Times

Dr. Neal Kaufman, director of Cedars-Sinai's Division of Academic Primary Care Pediatrics, examines Purevjargal, 1, hospitalized with the chicken pox. Under the transition to a market economy, the government pays for in-patient care but not out-patient treatments, which means marginally sick patients-such as youngsters with chicken pox-fill hospital beds for the free treatments and hard-to-get drugs. ©Gail Fisher Los Angeles Times

Record-keeping is sporadic, at best, which leaves doctors to consult makeshift medical files and patient memories to determine treatment. ©Gail Fisher Los Angeles Times

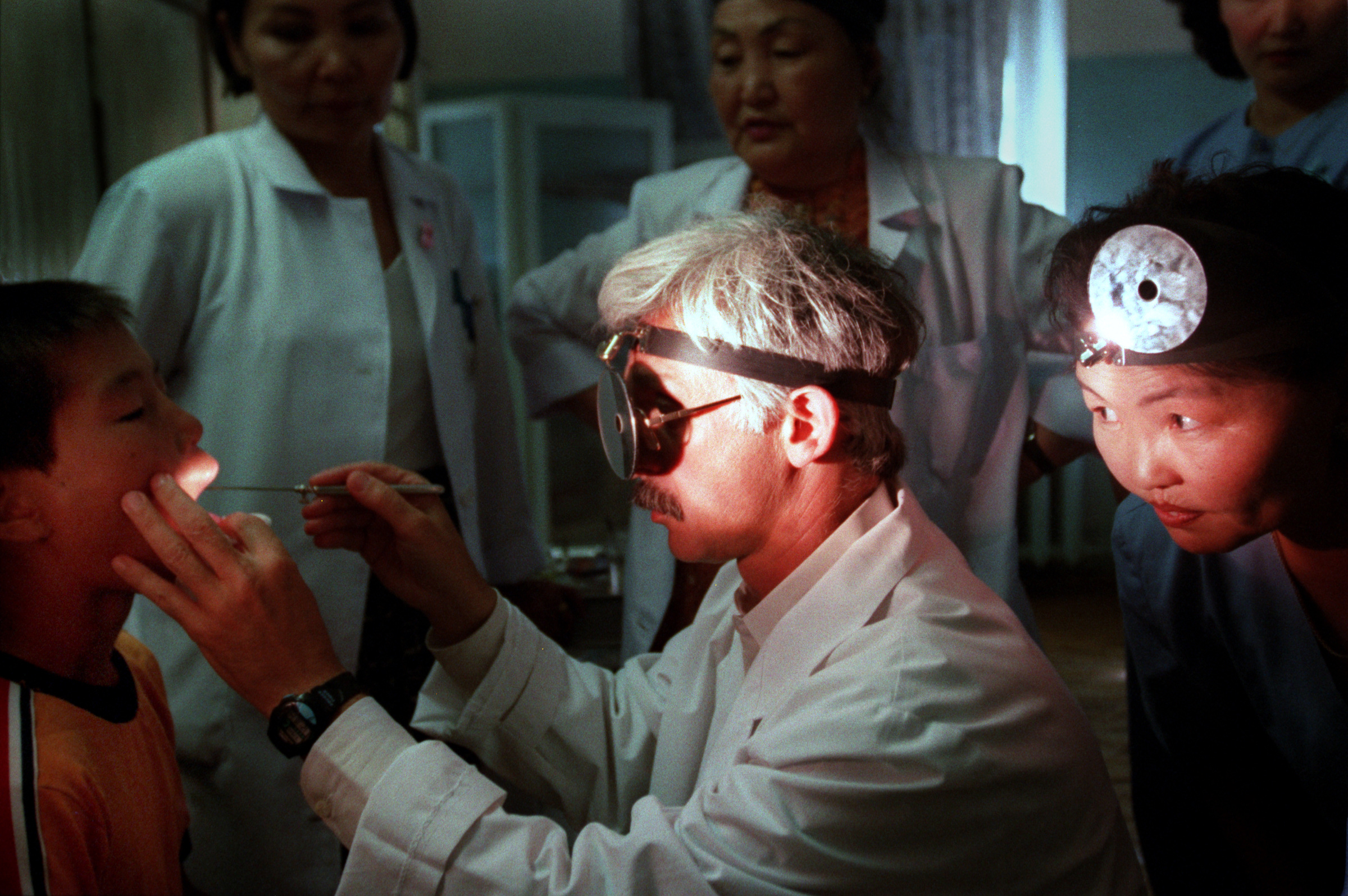

Dr. Kenneth Geller, who runs the Division of Otolaryngology at Children's Hospital Los Angeles, examines Batbaatap, 10 years old, who suffered a crushed larynx when he was kicked by a horse at his family's home in the Mongolian countryside. Remoteness impedes delivery of health care, a problem exacerbated by rural stoicism that leads to delays in seeking medical help. When Batbaatap was injured nearly two months earlier, doctors could have helped restore his voice. Now it's too late. ©Gail Fisher Los Angeles Times

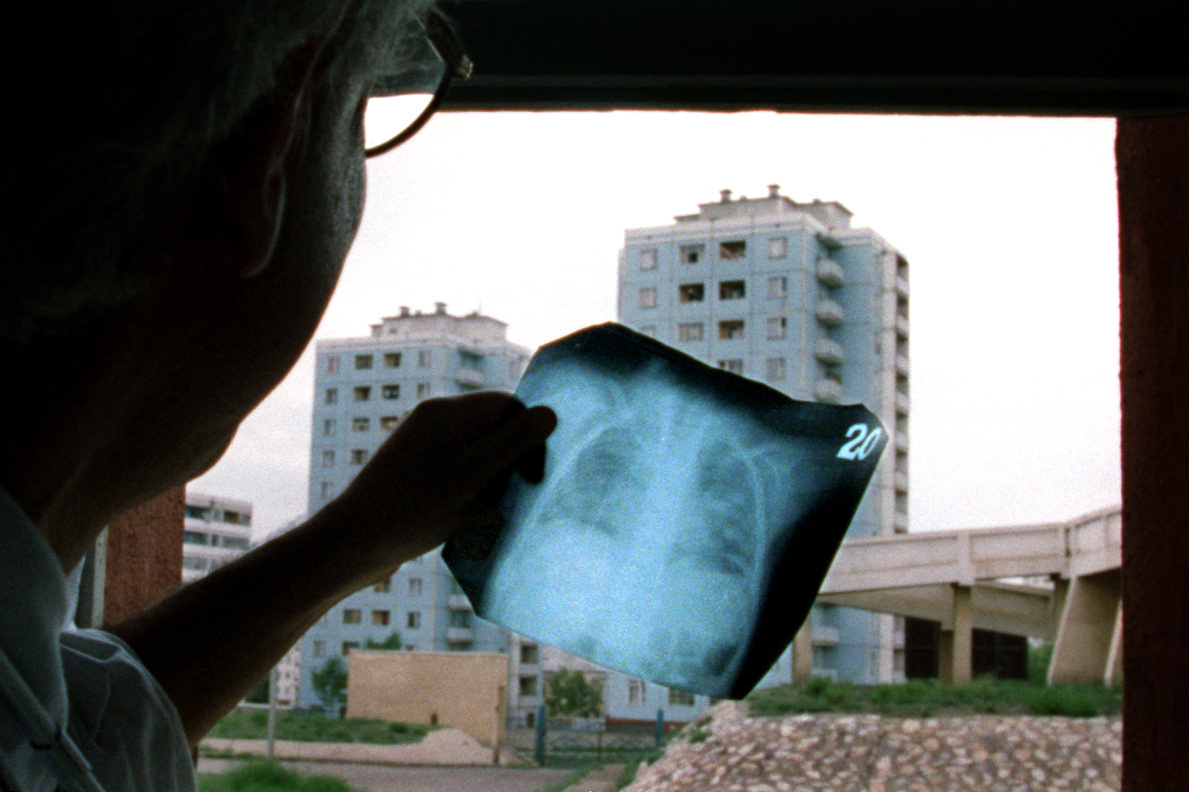

Dr. Larry Ross, associate professor of clinical pediatrics at USC and Children's Hospital of Los Angeles, uses a window to examine xrays of a child's lungs. The country has mostly rudimentary medical equipment. ©Gail Fisher Los Angeles Times

Nandin Ergene, 4, lost both eyes to retinal cancer, surgeries that the American doctors say likely saved her life. ©Gail Fisher Los Angeles Times

Because of the Mongolian tradition of swaddling babies during the first year of life, infants don't receive vitamin D from its natural source, sunlight. As a result, rickets, which causes bone malformations, is common among children. ©Gail Fisher/Los Angeles Times

Tcerenchunt, 2, suffering from a hernia, gets the once-over after his mother, Chimedtceren, brought him to a clinic in Tu Aymog, a small village medical facility about 80 miles from Ulaan Baatar. Just over half the national population of 2.5 million, live in cities.The rest lead semi-nomadic lives in the countryside, living off herds of sheep, goats and cows. ©Gail Fisher/Los Angeles Times

Right, Dr. Robert Greenburg is optimistic about improving treatment of cervical cancer in Mongolia. During the week his crew from Medicine for Humanity was in Mongolia, they helped reinvigorate a dorman screening program, and improve the way Mongolian surgeons perform life-saving radical hysterectomies. ©Gail Fisher Los Angeles Times